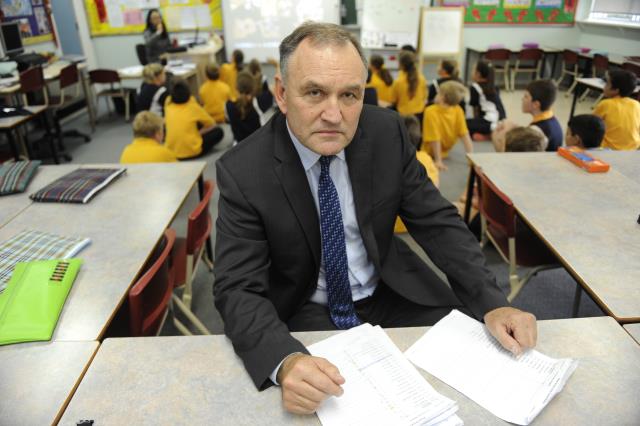

In light of Berwick Lodge Primary School’s principal of 35 years, Henry Grossek’s retirement, he remains one of the most outspoken local voices in the education department, from critiques to figures and policies at all levels of government and sectors.

Grossek has not been shy in the 55-plus years in the sector when it comes to making his voice known, with comments around NAPLAN, the 2010 criticism against a segment of the Building the Education Revolution (BER) program, to name a few.

“There wasn’t one single moment of time when it came to speaking out that I suddenly had a lightbulb moment,” he said.

“What I did notice, though, was that a key part of it was genetic; my father was very much into philosophy, a very well-learned man from Poland, and he used to say, ‘I may disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the end your right to say it’.”

Loosely based on French Enlightenment writer and philosopher, Francois-Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire and his quote on freedom of speech, it was something that stuck with Grossek, and something that he chose to live by.

On the BER, Grossek publicly challenged the federal government’s $16.2 billion program, where he highlighted inefficiencies and misallocations of funds.

From 2009 to 2012, he led a four-year national campaign for schools where he highlighted the poor deal, according to The Educator, that public schools were given under the BER.

In the larger scheme, Grossek strongly criticised the country’s approach to the ‘free-market model of education’ does not equate to a levelled playing field.

He has also fun a strong voice on the topic of teacher shortages in the state, where he has criticised competitive hiring practices that in turn undermine staff.

This voice did not just sprout from nowhere, however, as he recalled that he grew up in an environment where debate was encouraged, and while it created tension at times, they “never stifled in it”.

“We had disagreements, yes, maybe we walked out of that room with steam coming out of our ears sometimes.

“But it included in me the importance of being true to who you are, and in education, the biggest challenge is having to deal with different political parties in government.”

Grossek said that the myriad of political views, on what could be the best or what should be done, in terms of education and how it’s represented, ultimately make it a tumultuous environment.

“In public education, you have to be prepared to cope with a little bit of cognitive dissonance, where you’ve got to implement things that you don’t think are right,” he said.

With a Polish father and a German mum, during the post-war era of the Second World War, he said it had been difficult and conflicting to be a child in school.

But what also stuck with him were the words of a post-war confessional poetic piece by German Lutheran pastor, Martin Niemoller, and the silent complicity of German intellects following the Nazi’s rise to power.

Grossek recalled the poem, reciting that “first they came for the socialists – and I did not speak because I was not a socialist”.

“Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew.

“Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me.

“In a broad sense, that defined me, and it doesn’t mean I believe I’m right, but I believe that if I have a strong conviction about something, and I’ve done my research properly, then I should enter that debate and contribute,” he said.

Throughout his career, Grossek noticed that teachers and parents would speak about certain policies, but in the end, no one would publicly voice themselves.

What he also learned is that “ministers don’t like what you say sometimes”.

“I’ve had pressure on me throughout my career not to speak, but I’ve also found that in speaking, occasionally I think I’ve had an impact.

“I’ve also learned that some people have seen or heard it and said that, well, I don’t want to go down that path.

“But for me, I can at least go to bed at night and put my head to the pillow and think, well, I tried, rather than what if – I don’t like what if as a thought to go to sleep with,” he said.

When he decided, it was a revelation for Grossek that, through speaking out, as an ambitious young teacher, he had “no limits”.

He recalled that he had been told that “if I wanted to air my views, I could do that at the footy with a beer and a pie, but not in public”.

“I’ve been called names in public at times, but I’ve seen the times where my public speaking has been of systematic benefit.”

Grossek also admitted that there were times when he might have been over the lines, or have gotten some of his facts wrong, but ultimately, he sees utmost importance when it comes to speaking out.

In his retirement, he looks to remain an active voice in the education platform, already with a strong legacy set in Berwick and beyond.