Kite flying has always been a part of Mohammed Balkhi’s life.

As a child he would run through the streets of Kabul with his friends sending brightly-coloured, home-made kites aloft into Afghanistan’s azure skies.

At age 12, Mohammed started making his own kites as the traditional Afghan custom of kite flying took hold and became a passion.

Now resettled in Dandenong as a refugee, he hopes to turn his passion into a business.

“I grew up in central Kabul where kite making and flying was a thing that was very common. In Afghanistan, we did it for fun but now I would like to create a business out of making and selling kites,” Mohammed said.

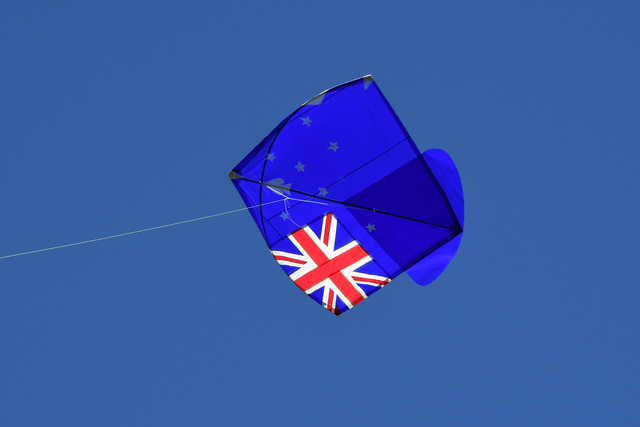

His kites are made from thin paper connected by a thin string to a hand made spool. Unlike western kites which are held static against the wind, Afghan kits are designed to be run with.

“We get someone to hold the spool and then we throw the kite up in the air. The wind coupled with special movements of the string makes for a lovely view of dancing kites in the sky.” Mohammed said.

Mohammed glues together coloured pieces of paper to form intricate and colourful designs, making the kites decorative items as well as flying machines.

They are held together by thin pieces of treated wood from Afghanistan. The kites range in size from 20cm square up to a metre square.

Mohammed worked at a range of jobs in Afghanistan, most recently in a printing and copying shop.

But after the fall of Kabul, Mohammed and his family were forced into hiding.

“My father worked as a guard at the Australian embassy in Kabul, so his association with a foreign government made him a potential target of the Taliban,” Mohammed said.

“We were forced to lay low and, for a year, we were in hiding. We couldn’t risk being identified by the Taliban. At the same time, we were trying to get passports, so we could leave.”

After securing passports, Mohammed and his family spent ten weeks in Iran waiting for visas to come to Australia. Mohammed’s father’s connection with the Australian embassy made the visas possible.

Mohammed, his wife and two children, as well as his parents arrived in Australia two years ago.

He says they are grateful to have found safety in Australia and he sees a bright future for his two children, aged three and five months.

But Mohammed suffers from a herniated disc in his back and is unable to do physical work or even sit for long periods.

“Making and selling kites is way for me to work and earn a living,” Mohammed said.

He has already sold kites at local festivals and among the Afghan community in Melbourne’s south-east.

He is being supported to grow his fledgling business by migrant and refugee settlement agency AMES Australia.

Kite flying in Afghanistan was banned by the Taliban during the 1996 – 2001 war. It was against the law for several years, but after the collapse of the Taliban government, it became legal again.

Many young Afghans are attracted to the sport and the best season for kite flying in Afghanistan is during autumn because of the favourable winds.

The most common place to fly kites in Kabul is in Chaman-e-Babrak, a park in the north of the city, where many kite-flying competitions are held.

Kids, teenagers, adults, and older people come from all around Afghanistan and to participate in these competitions.

In Afghanistan’s cities, the sky is filled during these competitions with hundreds of brightly coloured kites soaring high into the air going from one side to the other.

Khaled Hosseini, the author of The Kite Runner, a novel that explores life under the Taliban as well as kite flying, writes about the sport of kite fighting.

“When an opponent’s kite is cut free, it flutters like a colourful, dying bird into the far reaches of the city,” Hosseini wrote.

Details on Mohammad’s kites, 0476 279 444.