By Cam Lucadou-Wells

More people in Berwick ought to know the heroic and tragic name Harry Graham.

Graham is the only Test cricketer from Berwick Cricket Club.

In his pomp – in the 1890s – he was regarded as one of the world’s best batsmen, author Ronald Cardwell said.

He made a century on debut at Lord’s – the first Australian cricketer to attain the feat.

“His batting style was reminiscent of noone seen before him,” Mr Cardwell said.

“He used to dance down the track and play through the covers. He played his shots.”

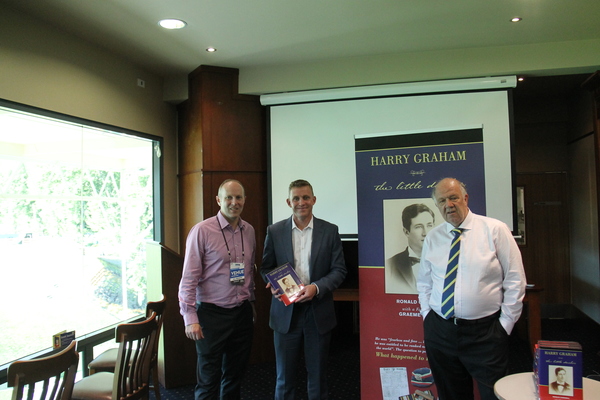

Graham has been immortalised in Mr Cardwell’s book The Little Dasher, with the Australian launch of the book at the Melbourne Cricket Club on 12 April.

The stylish batsman – renowned on wet-weather pitches – deserves to be the equal of the town’s first Olympian, Edwin Flack, Mr Cardwell says.

Like Flack, Graham deserves a prominent statue in Berwick’s town centre.

Graham had boarded at Berwick Grammar School as a student, and kicked on as a talented country footballer who played with his brother at Melbourne Football Club.

At Berwick Grammar, his cricketing talent was nurtured by schoolmaster Edward Vieusseux, who was also a highly regarded player.

“I’d suggest that Graham had natural talent but learnt to be a cricketer from the principal at the school,” Mr Cardwell said.

“He’d be hitting a ball in summer, and kicking a ball in winter.”

Graham later played for South Melbourne Cricket Club – which has since re-located to Casey – and Melbourne Cricket Club.

Yet as Mr Cardwell demonstrates, there is an epic tragic dimension to Graham’s life outside cricket.

He said he needed to know why this gifted sportsman succumbed to alcoholism after his Test career and died in a New Zealand lunatic asylum as a 41-year-old in 1911.

Mr Cardwell enlists a psychologist and medical expert to diagnose Graham’s demons within the book.

“Society didn’t know how to deal with it so put him in a mental asylum,” Mr Cardwell said.

“Because treatment wasn’t great in there, it was only a matter of time that he died.”

The simple reason for Graham’s descent was a lack of vocation, Mr Cardwell said.

Graham didn’t have to work during his cricket retirement, living for 15 years off the substantial riches of two Test tours to England in 1893 and 1896.

He tried his hand briefly at his father’s hairdressing business, on goldfields, in a stock agent’s office, and as a salesman – but mainly he played cricket, socialised and “wasted his time”.

“Alcohol became his friend. It effected his form, him personally and his life.”

Graham’s reluctance to look into the camera in photographs showed a shy person, perhaps with not many friends, Mr Cardwell surmises.

“He was never married, as far as I know.”

It’s not uncommon for retired cricketers to befall such tragedy – including modern sportsmen, Mr Cardwell said.

“Because a lot of players grow up in the game and become cricketers straight out of school, they don’t have a trade.

“They don’t do a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay.

Graham’s roller-coaster life is salutary, Mr Cardwell says.

It reminds us that retired elite sportspeople need ongoing support and don’t suffer when they hit life’s “realities”.