In 2020, Star News Group journalist DANIELLE KUTCHEL received funding from the Melbourne Press Club’s Michael Gordon Fellowship to explore mental health in asylum seeker and refugee communities. Below is part two of the story.

When *Sam realised he was experiencing mental health issues, he knew he had to get help.

It was 2013, and he’d just had his first major anxiety attack.

On the outside, Sam had it all; he’d made it to a senior management level at his job and had settled down to life in Australia with his wife and family.

But the anxiety attack shook him deeply.

He felt foggy and experienced a loss of identity, and worried he was losing his mind.

He felt trapped, out of control, worthless, angry – and guilty.

“I didn’t know what it was all about – although I had studied bits and pieces [about mental health], I had never experienced such a thing personally,” he said.

“I was always a bright kid at school, always funny with friends…always cracking jokes, a full-of-life kind of guy.

“So when the anxiety happened, I was in denial. I didn’t know what had happened to me. The world became dark and my stressors kept building up.”

Sam visited his GP to find out what was wrong, and was referred to a psychiatrist.

It wasn’t long before the professionals had traced his mental health issues to their roots, and found that they were at least partly derived from his traumatic experience in leaving a war zone in Afghanistan with his family as a child.

The stress of his adult life had compounded that trauma.

“It was a combination of leaving Afghanistan, resettling into another country with a different language and culture…then coming to another country, and again the culture shock and financial stresses and some mild relationship issues,” Sam explained.

His condition deteriorated in 2013 and 2014 and he was hospitalised for five weeks. After being discharged, he attended a recovery class at the hospital, a day a week for almost two years.

But a second anxiety attack hit Sam in 2018 that was even worse than the first.

This time round, he received ECT – electroconvulsive therapy.

To this day he is still struggling, he said, trying hard to recover fully and get back into work. Of course, the pandemic hasn’t helped things.

“Once you get anxiety and depression, you live in your mind; you don’t live life as it used to be,” he explained.

But he knew he had to get help.

“I had to do something about it; that much I knew,” Sam said.

Sam was lucky, in a way, given he knew which people to approach for help with his mental health.

But not all new Australians are so fortunate.

When you’re unfamiliar with the health system of your new home, you may find it difficult to know where to go.

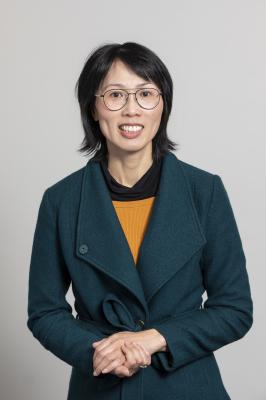

Dr Judy Tang, clinical neuropsychologist and a commissioner at the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC), said there was often no set pathway for refugees and asylum seekers to access support when it was needed.

“Ideally, they get set up with services to support them in other areas, like housing or job seeking, making sure they’re attending English classes and helping them understand the medical or health system itself,” Dr Tang explained.

“Ideally those people like the GPs or other support services are able to link them in with mental health and support services if they feel that’s needed.”

Viv Nguyen AM, commissioner and chairperson at the VMC, added that many newcomers might be unfamiliar with the idea of getting help with their mental health.

“Accessing things like mental health support and other services that refugees aren’t familiar with in their country – they might not know where to go, might not think it’s a mental health issue and might let it sit for so long and by the time they access or realise that they can access or are able to access help, it might be a bigger challenge for them and our society than if we had identified it in the early days and supported them to settle and integrate.”

But improvements can be made to this system, Dr Tang said – like better pathways, so that people don’t have to wait until they get to “the end of their tether” to access support.

“What usually happens…is because there’s no clear understanding or a more direct pathway to access mental health support or wellbeing, the individual or family member might feel quite isolated and not seek that help until it’s much further down the track.”

In Australia, if a person has Medicare, they can access a mental health treatment plan of subsidised or free psychological services.

But there are many in the community without access to Medicare, Dr Tang said, and for those with visa issues or other barriers to the nation-wide medical cover, they don’t get access to those treatment plans.

In those cases, they can turn to support or advocacy services who will be able to point them in the direction of medical help.

Though, as Dr Tang cautions, accessing support often comes down to being able to afford it.

In Sam’s case, his GP and psychologist were able to provide him with the help he needed.

His journey is ongoing; he said he always knew in the back of his mind that his feelings were only temporary, and tried to be there for himself first and foremost.

But professional medical guidance and medication have also been integral to his treatment.

Sam believes that another barrier to accessing mental health support in refugee and asylum seeker communities is a lack of culturally appropriate resources.

He was fortunate to have the support of his immediate family, but mental health is still subject to dark stigmas and many people don’t share the truth of their condition with their wider social circle, he said.

He said more awareness of mental health resources is needed for the whole community.

“If I had come across even a small flyer that talked about mental health and had a [support phone] number in there, at the time when I had this attack with the symptoms, I would probably not have panicked about my condition,” he said.

“I think it would be a fantastic idea to bring more awareness to the community, and to have some key points for people to know, something as little as ‘if you’re feeling XYZ, please make sure you speak to people’, and provide another resource. That way, they can go there and be reassured.

“But I learned a lot, the hard way.”

Part three of this story will explore the stigmas that still dog discussion of mental health, and how these are being countered by various community groups.

*Not his real name. Sam wanted to withhold his name as he does not want to add to the worry of his community.

If you need to talk to someone, please reach out to:

Lifeline – 13 11 14 or lifeline.org.au

Beyond Blue – 1300 22 4636 or beyondblue.org.au