On 16 February 1983 at 3.24pm, a bushfire started on Birds Land near Mount Morton Road at Belgrave Heights.

The temperature at 2pm was 40.5 degrees. The relative humidity was 14 per cent with wind from the north at 25km an hour.

The fine fuel moisture content at Kallista was estimated to be an extremely low nine per cent and the Drought Index was 383.

Unsurprisingly, the Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) was extreme.

It’s unclear how the fire started, but most suspect arson.

The fire was fanned by the hot northerly winds and quickly headed towards Harkaway, Narre Warren East and Guys Hill.

Within four minutes, houses were burning in Mount Morton Road, and by 4pm the fire had crossed the Belgrave-Hallam Road.

Some spot fires were recorded 30km ahead of the main front.

Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) and National Parks Service (NPS) crews from Kallista, Ferntree Gully, Olinda and Gembrook were immediately deployed to join a large contingent of CFA crews. Other FCV districts from Central Division came too.

It’s worth noting that well away from the media’s gaze, and therefore largely unreported, the FCV was already heavily committed to a large 100,000 hectare campaign bushfire, which had started two weeks earlier at Cann River, in the far east of the state.

Other bushfires started in state forest near Warburton and Cockatoo later on Ash Wednesday which split the remaining FCV and CFA resources.

There were hundreds of fires reported that day, with major blazes in South Australia and western Victoria as well.

Virtually everything and everyone that was available from the Forests Commission were committed to bushfires across the state. There were no reserves left.

It was a manic and confused afternoon. Radio channels were choked and communications were poor.

It’s fair to say that the FCV, NPS, CFA and Victoria Police which all operated independently on separate radios and with different command arrangements were overwhelmed.

In many cases residents had to fend for themselves as the fires broke communications, cut off escape routes and severed electricity, telephones and water supplies.

The situation was made worse because there seemed to be no distinct fire front, but instead hundreds of rapidly developing spot fires that eventually joined. The average Rate of Spread (ROS) in the forest fuels was estimated to be about 5km an hour. It was faster on the grass.

Around 8.50pm that evening, the fire had travelled over 20km and crossed the Princes Highway near Officer, when a dry blustery south westerly wind change of about 110km an hour hit the Upper Beaconsfield area.

With the violent wind change, the entire eastern flank was lost, and the fire roared up from Guys Hill and wreaked havoc through Upper Beaconsfield, tragically taking many lives and properties along the way.

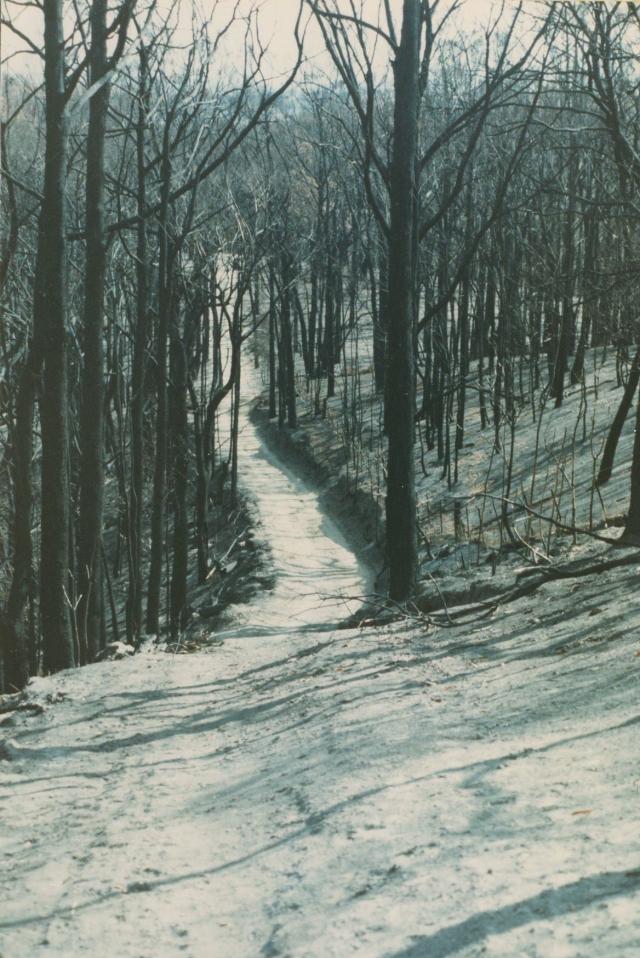

Twelve CFA firefighters, in trucks from Narre Warren and Panton Hill, also lost their lives on a narrow bush track at the Critchley Parker Junior Reserve when the fire overran them.

Prior to the wind change, Forests Commission tankers and crews had been specifically instructed not to leave the relative safety of wider roads, where they could turn around, and to “keep one foot in the black” – meaning be able to quickly retreat to burnt ground.

Around 2am on Thursday there was a light sprinkling of rain upon the blackened fire ground.

The bushfire eventually stopped by the southern shore of Cardinia Reservoir and extended nearly as far as Gembrook, and by about 4.30am on Thursday the fire front had all but stopped.

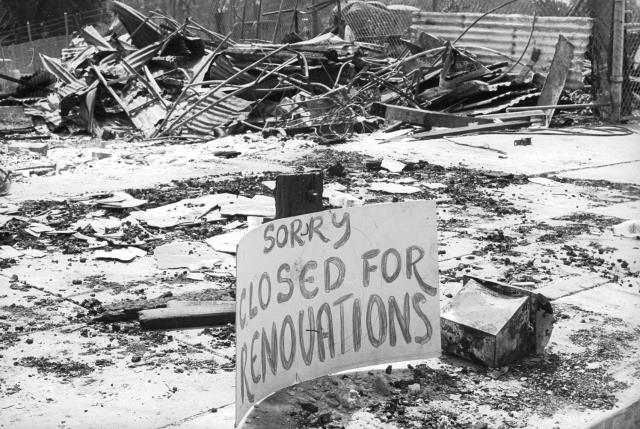

Over its 13 hour rampage a total of 9200 hectares was burnt, 21 people died and 230 homes were lost.

A memorial was later built by the CFA and FCV at Critchley Parker Junior Reserve to honour the CFA crews.

*Peter worked at the Forests Commission in 1983 and was at Upper Beaconsfield during Ash Wednesday.