John Goldspink has a life to tell you.

The 98-year-old Pearcedale resident took the lead in this year’s Cranbourne Anzac Day march as the eldest member who served the country in the Dandenong-Cranbourne RSL.

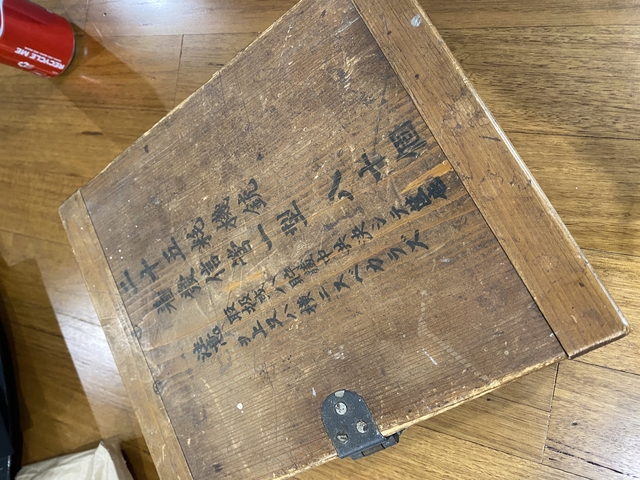

He still treasures a wooden casket from the Second World War and keeps the physical memories inside: an enrolment form, paperwork, paybook, a will, and several dog-eared yellow pictures from the old days.

The origin of the casket has long been forgotten, but the Japanese characters carved into the lid, “25 wearable machine gun. 80 fuse type”, declare it could be a grenade box.

On the back of the lid, English words finally emerge. Crooked but identifiable, they say “19 Australian Field Ambulance Unit”, where John served during the war.

Growing up in Tumbarumba, a town in New South Wales, John was enlisted in the medical department on 22 March 1944 when he was an 18-year-old teenage boy. It was a voluntary move. Long inspired by his neighbour who returned from the First World War, John felt compelled to defend Australia.

He later had infantry training in Cowra, New South Wales and medical training in Darley, Victoria. On 15 January 1945, he was shipped to Bougainville, a part of Papua New Guinea.

“The Japanese, after the Pearl Harbor incident, have come down through Malaysia and all those other ones. They have started to come down,” John recalled.

“So the Australian forces at the start bolstered or defended the islands, and then the Americans eventually came and helped.

“After that, some Australians went over to Europe, but the main contingency of Australia would have been Malaysia and the islands.

“Papua New Guinea was like the last stand for Australia.”

“I assisted in operating on the wounded diggers,” he continued.

“I can always remember the first three wounds I ever saw. The first was shot through the arm. The second was shot in the stomach and the third was the head.”

John was discharged on 30 April 1947 after being shipped back to a hospital in Sydney. He lost the hearing of one of his ears during the service due to an infection.

The war imprinted indelible marks on his memories. There were mixed feelings. He still remembers some good times in the army.

“When I was in the hospital in Sydney, they had their own movies and all sorts of things. But we didn’t have ice cream. The Americans used to have ice cream. We didn’t,” he joked.

But grey moments were more of the usual. A black-and-white picture from the time may have proved that. It was the moment of a volcano erupting in Papua New Guinea. Addressed to an unknown, John wrote a line on the back: “I hope you like it because I am beginning to hate the sight of it.”

“I was lying in the back when I was looking at it. It was a pretty clear night. I was on the ground anyway. I felt the bed shake,” he recalled.

“I was homesick, and with all the stuff that was going on.

“I was homesick for a while, but you would’ve been over that in the end.”

After the war, John returned to his hometown and went back to his old normal job: making boxes.

The army helped him secure a new painting job. After that, he worked for a local builder for a while.

He started a family, created his own business later in his life, and moved down to Victoria. The family lived all around Melbourne: Carnegie, Clayton, Dandenong, and eventually Pearcedale where John went into the cattle business.

He never picked up nursing, his army profession, after the war.

“I thought, I’ve seen enough blood and guts,” he said.

“I just couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t continue doing that on a daily basis.”

But attending Anzac Day has always been a routine and a must.

“The Anzac Day is a good day to remember, trying to get the young people to think about what we all went through,” he said.

“As long as we remember.”