The City of Casey has been identified as Victoria’s family violence hotspot, with police revealing nearly 7000 incidents recorded so far this year, the highest volume of reports for an LGA in the state.

This figure formed the centrepiece of discussion during the Neighbourhood Police Forum at Bunjil Place on Thursday, 21 August, where senior VicPol officers outlined the scale of the crisis and its flow-on effects throughout the community.

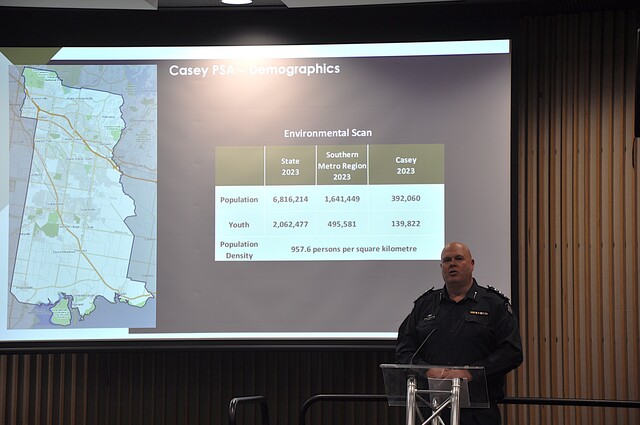

Rod Maroney, the specialist investigation and support inspector for the division encompassing Casey, Dandenong and Cardinia, said that the reason why numbers are so high in Casey is because “Casey grows”.

“The reason why it occurs is because Casey is growing every day, and we are getting a lot of young families moving into the area, living with the pressures of family environments such as kids, schooling, employment, the cost of living and so forth.

“So when we talk about those numbers, although they seem quite large and they are, a lot of those are very much first-time reporters,” he said.

For Victoria, family violence remains the most significant crime theme across the state, both in sheer numbers and in terms of the lasting harm that is caused.

What was greatly emphasised throughout the night, however, was that VicPol treats family violence as a crime, not as a dispute amongst individuals.

This came as Maroney, as well as the other officers, spoke on the cultural shift within the organisation, treating family violence as more than just a social issue, as well as enforcing a zero-tolerance approach to breaches of intervention orders.

Maroney further added that the larger percentage of incidents are of the lower level, such as the mentioned first-time reporters.

“We get involved with them, our members come out, fill in the forms, and from those support services will be brought in,” he said.

“The vast majority of the time, those support services are enough to help families so that we don’t have to see them again.”

VicPol works closely with a wide range of support agencies and organisations, such as Orange Door, based in Dandenong, but also Windermere, Wayss, Relationships Australia, and Southern Integrated Family Violence Partnership.

“The stats you’ll see here are increasing each year, it’s not unexpected; we are no different to any other area in a sense, we just have a large, growing population,” Maroney said.

“Yes, we are getting a lot of family violence, but anyone who gets an intervention order, we make sure that they’re held to account for that.

“There’s no such thing anymore in Victoria Police about how it’s a minor breach, or that it’s a technical breach; we don’t stand for that anymore.

“If there is a breach, the offenders are held to account; it’s very simple for us now, and that’s part of that cultural shift.”

Building on intervention orders, stats on the night also detailed that throughout the division, there are roughly 70 intervention orders that are issued by the Dandenong Magistrates’ Court.

Maroney said that while the numbers are a lot, “it’s not all bad”.

“Because what it means is that our victim survivors are actually coming forward and reporting to us, which is what we want.

“If they don’t report to us, we can’t intervene, and we can’t stop that family violence from continuing to occur.

“Victim survivors are being assaulted, stalked, and properties are being damaged; it leaves a lasting effect on children, and we treat it as it is, a crime,” he said.

Ben Gordon, the officer in charge of the Family Violence Investigation Unit, explained that while Casey records thousands of incidents each year, only a small portion are handled by his detectives.

His unit, the FVIU, is tasked with investigating around five per cent of the most severe cases, such as incidents that require a specialist investigative response and strong prosecutorial outcomes.

Gordon said that the unit specifically looks at two core areas: ensuring that the most serious crimes are investigated to a high standard and managing high-risk offenders through offender management plans.

“I don’t want to be all doom and gloom, but the matters that come to us are quite severe,” he said.

“They do need a specialist response, and there are victims within our community that need our specialist response in order to keep them safe.”

He also highlighted the importance of inter-agency collaboration, noting that the division also partly organises the Risk Assessment Management Panel (RAMP), which brings together police, corrections, child protection and family violence services to share real-time information on the most dangerous cases.

Shane Wright, the divisional family violence coordinator, holds a unique role that was created in response to the volume of incidents in Casey.

Wright described it as the link between frontline officers, station-based family violence liaison officers and external agencies such as the courts and Orange Door.

When asked by a member of the gallery about the percentage of family violence offenders who are repeat offenders, he said that it’s a figure of 3.2 per cent for 2025.

“Those [victims] are the ones that need additional support from Victoria Police, as well as external agencies,” Wright said.

“They’re the people that we’re really trying to reduce and provide that extra support to, because whilst the initial contact with police is a very traumatic time, we try to put things in place with those external agencies to prevent that from occurring.”

Despite these efforts, however, Kay, a local specialist family violence counsellor who has worked in the sector for more than a decade and has lived experience herself, spoke about the difficulties some victims still face when approaching police stations.

Speaking on one client, Kay said that they had been told by an officer at the desk “that she didn’t need another family violence intervention order”.

“That she probably didn’t need the last one, and that 50 per cent of women who come in to report are liars, and anyone can get an intervention order these days.

“That was really disheartening for that person; she was absolutely devastated,” Kay said.

Kay also raised broader concerns about the way the victims are treated at the counter, where she recalled that they are often required to provide personal details in public spaces, which she described as retraumatising.

In response, Maroney once more emphasised the importance of the mentioned cultural change, apologising first on his own behalf to Kay and her client, and saying that officers have “undergone a lot of training”.

“Every member in this room has been trained in relation to family violence, and every member here and on the road knows that when a victim comes to report, the courage it takes for them to do that, we have to take it seriously,” he said.

Ultimately, the scale of the issue in Casey underscored why family violence was placed at the top of the forum’s agenda, with officers undergoing cultural change, taking on calls with utmost importance.

The demand remains relentless, with authorities urging the community to continue reporting, adding that help is available.

If you or someone you know is in direct danger, call Triple 000 for police and ambulance help.

For access to 24-hour national sexual assault, family and domestic violence counselling, contact 1800RESPECT.

For access to VicPol resources on family violence, visit www.police.vic.gov.au/report-family-violence